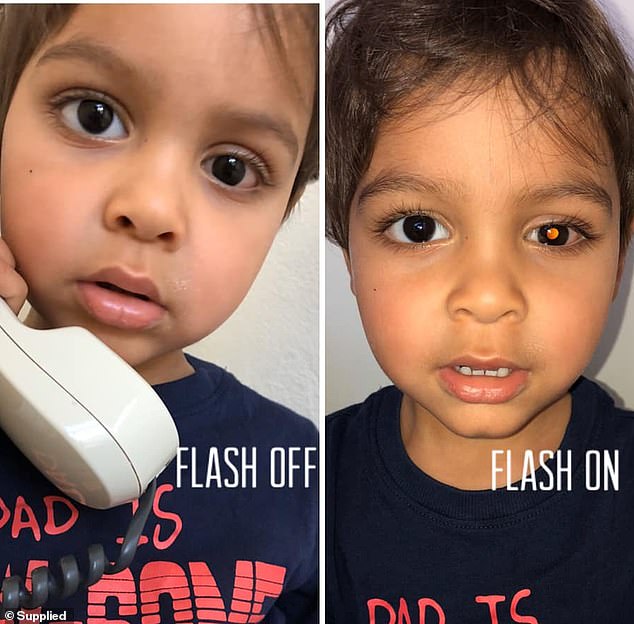

The mother of a two-year-old son who lost one eye to a rare type of cancer advises parents to keep an eye on their children by taking pictures with a flash, which is often the first and only indication that a tumor is developing at the back of the eye.

Rocky, Kara Sefo’s son, was a “dream baby” who slept sweetly, played energetically, and breastfed smoothly.

As a result, the events manager from Newcastle, two hours north of Sydney, wasn’t too concerned when her four-month-old began developing a lazy eye on a regular basis in late February 2018.

Ms. Sefo, 43, turned one evening while washing dishes and observed a reflected patch in her son’s left eye that looked like a marble. Her gut instinct alerted her that something far worse was going on.

Ms. Sefo received the terrible news on June 21, 2018, a Wednesday, that Rocky had retinoblastoma, an early childhood cancer, growing behind both of his eyes. At the moment, he was eight months old.

Rocky’s left eye was removed in March 2020, when he was only two years old, after months of chemotherapy, laser treatment, and cryotherapy failed to eliminate cancer from his tiny body. The battle started with the diagnosis.

“I remember doing the dishes one night while he was playing around and saw an area that looked like a marble or cat’s eye. Ms. Sefo told Daily Mail Australia, “Looking back, I realize it was the retinoblastoma being hit by light.”

Rocky was six and a half months old when a chiropractor giving a routine examination on him noticed his lazy eye and advised Ms Sefo to take him to their GP for a checkup.

Rocky was referred to an ophthalmologist to rule out any underlying issues, but the specialist found nothing abnormal.

According to an ultrasound, he had 90 percent vision in his right eye but only 10 percent in his left eye, which had an out-of-control tumor in the retina, the area of the eye that receives light at the back.

Medical doctors immediately began Rocky’s six-month chemotherapy treatment plan in order to eradicate the illness before it spread to his brain and central nervous system.

Ms. Sefo remembered, “They genuinely informed us that if that happened, we would lose him.”

“I just started crying because I guess deep down I knew there was something wrong all along. I remember feeling as if I were dreaming when I entered the oncology ward and saw all these children hooked up to tubes.”

Retinoblastoma is a rare type of cancer that develops at the back of the eye in children under the age of three.

While the particular causes are unknown, doctors do know that cancer is linked to a faulty RB1 gene, which can be inherited from one or both parents or develop independently in the child after birth.

Rocky is one of approximately 750 Australian children under the age of 14 who are diagnosed with cancer each year.

Retinoblastoma symptoms wax and wane, appearing and then abruptly disappearing, and are frequently misdiagnosed as common pediatric infections, making diagnosis difficult and frequently leading in lengthy delays in discovering the condition.

Children with retinoblastoma have a high chance of survival because the illness has not spread to the optic nerve, brain, or spinal cord. As a result, early detection can mean the difference between life and death.

The most evident danger sign is a pupil that becomes white or yellowish instead of red when exposed to light, which is why Ms. Sefo urges parents to frequently photograph their children with the flash on.

Other symptoms of the illness include drooping or staring eyes, a hot, hurting, or enlarged eyeball, and cloudiness in the iris, the colored region of the eye.

Ms. Sefo had horrible stomach pains the day Rocky was diagnosed, which she attributed to the stress and anxiety of discovering such devastating news.

She was sent to the emergency room after feeling so unwell that she couldn’t move. After finding that her appendix was about to explode, doctors promptly removed it.

“I couldn’t even pick him up,” she explained, “and Rocky was starting chemo, so it made things even more difficult.”

Rocky started a less invasive course of treatment with monthly laser and cryotherapy sessions to eliminate the stubborn tumors that remained behind his left eye after six months of chemotherapy.

But by September 2019, the disease had grown too far, and Rocky was forced to undergo a three-month round of chemotherapy, this time delivered directly into his eye.

Retinoblastoma is an uncommon type of pediatric cancer that occurs when abnormal cells in the retina—the back of the eye that detects light—grow out of control.

It can impair one or both eyes, and it usually affects children under the age of three.

While the particular causes are unknown, doctors do know that cancer is linked to a faulty RB1 gene, which can be inherited from one or both parents or develop independently in the child after birth.

Every year, 750 Australian children aged 0 to 14 are diagnosed with cancer.

Australia has one of the best survival rates in the world, with an average five-year survival rate of 84 percent, ranking below Germany, the United States, South Korea, and Canada among the G20 nations in terms of the prevalence of childhood cancer.

In Australia, leukemia is the second highest cause of death in children, accounting for 22% of cases, followed by neuroblastomas, including retinoblastoma, at 13%. Central nervous system cancers, particularly brain tumors, account for 39% of all instances.

Long-term survival rates are high since the disease has not yet spread to the optic nerve, brain, or spinal cord; consequently, early detection can mean the difference between life and death.

Rocky stopped responding to medication unexpectedly in February 2020, despite the fact that it had previously appeared to be working, and doctors were compelled to arrange an eye removal surgery in late March.

“We tried to think of it as the end of something and the beginning of a new chapter for Rocky’s life,” Ms. Sefo said.

“This experience has shown me how strong a mother’s intuition is; you just know something isn’t right on some level,” she explained.

The procedure was “extremely stressful” for Ms. Sefo and her family, but Rocky, whom she refers to as her “little champion,” carried on as usual.

According to her, the patch he had to wear after having his eye removed was what worried him the most, and once it was removed, he resumed functioning normally.

Rocky’s struggle with cancer has had an impact on Ms. Sefo’s path.

She took a snapshot of Rocky with the flash on one hour before removing his eye to inform other Australian families about retinoblastoma. She is now an outspoken advocate for children with cancer.

Aside from the camera flash, the only other means to identify this is to have every child’s eyes dilated at six weeks old, according to a California statute, she added.

Ms. Sefo plans to launch a campaign in Australia to have similar legislation passed.

“The test they run in the GP clinic is simply not good enough,” she added. “Something has to change.”

In the meantime, take a flash photo once a month. It’s the best test we have right now.