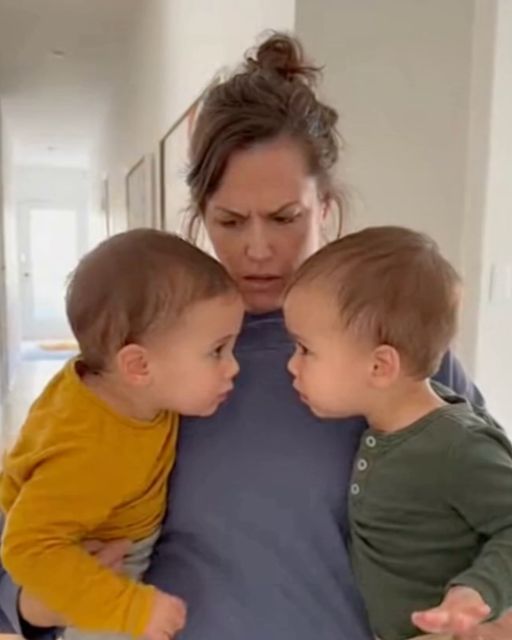

The weight was familiar. Twenty pounds of toddler on my left hip, twenty on my right.

My sons, Leo and Evan, were locked in a war of babble, their little bodies tense in my arms.

It was the usual two-year-old stuff. A squabble over a toy, probably.

But the sounds were wrong.

It wasn’t crying. It wasn’t screaming. It was a string of clicks and sharp, guttural coos. A rhythmic back-and-forth I’d never heard before.

Leo would let out a rapid triplet of clicks, his eyes narrowed, pointed at his brother.

Evan would immediately answer. A low, vibrating hum from the back of his throat. A dismissal.

I bounced them gently. “Hey, hey, knock it off, you two.”

They didn’t even register my voice. It was like I wasn’t there. I was just the chair they were sitting in.

Then I started to notice the hands.

Tiny gestures. A finger flicked. A thumb jabbed towards the ceiling. Each movement seemed to punctuate their strange, alien syllables.

My stomach felt hollow. This wasn’t a tantrum.

This was a conversation.

I stopped bouncing and just stood there in the quiet hall, a living scaffold for their secret summit. The air grew thick. The sounds they made were precise. Intricate. Too intricate.

Leo unleashed a final, desperate-sounding volley. A cascade of clicks and whines that lasted a full five seconds. It sounded like a closing argument.

Silence.

Evan stared at his brother. His face was perfectly calm. He took a slow breath.

And then he made one sound.

A single, deep, resonant pop from his throat.

It was a sound of absolute finality. A gavel striking wood.

Leo slumped against my shoulder. The tension went out of his body in a whoosh. He didn’t cry. He just went quiet, his argument lost.

I looked down at the two faces I knew better than my own. They weren’t looking at me. They were looking past me.

And I realized I wasn’t holding my children.

I was holding two strangers who just happened to live in my house.

I carried them into the living room and set them down on the soft rug. They immediately went to opposite ends, a silent truce in effect.

My husband, Daniel, came home an hour later. He found me sitting on the sofa, just watching them.

“Everything okay, Sarah?” he asked, loosening his tie.

I tried to explain. The clicks. The gestures. The final, definitive pop.

He smiled, that tired, gentle smile he always had after a long day. “It’s just twin talk, honey. They all do it.”

But I knew this was different. “No, Daniel. This was a real language.”

He kissed my forehead. “They’re two. Their language is ‘I want that truck’.”

I tried to show him later that evening. But they were quiet, playing with their blocks, making the usual baby noises.

It was like they knew I was watching. They knew I was listening.

For the next few weeks, I became a spy in my own home. I started leaving my phone in the corner of their playroom, recording audio.

I’d listen back at night, with headphones on, while Daniel slept. The house would be silent except for the secret world pouring into my ears.

It was all there. Long, flowing conversations. Quick, sharp exchanges. There were patterns, repeated sounds that must have meant something.

One click-whistle combination always seemed to happen before they started building a tower. A soft hum was always followed by one of them grabbing the blue blanket.

I was mapping a foreign country. A country of two.

The day Daniel finally believed me was a Tuesday. I had just finished childproofing the kitchen cabinets with those magnetic locks you need a special key for.

I left the magnetic key on top of the fridge, well out of reach. Or so I thought.

Later, I heard them from the living room. It started again. The clicks. The guttural chatter.

I peeked around the corner. Leo was standing by the counter, pointing up at the fridge. He let out a series of high-pitched chirps.

Evan was over by the pantry. He looked at the broom leaning against the wall, then back at Leo. He replied with a low rumble.

It was a plan. They were making a plan.

Leo went to the silverware drawer he could just barely reach. He pulled it open and began making a clatter.

While my attention was on Leo, Evan toddled over to the broom. He wasn’t strong enough to lift it, but he managed to knock it over. It fell with a clatter, pointing roughly towards the refrigerator.

He then started crawling along the handle. Leo, his diversion complete, scurried over and pushed from the other end.

Together, they angled the broom handle just so. The bristles nudged the magnetic key.

It slid across the top of the fridge and fell to the floor with a soft plastic click.

Evan picked it up. He walked over to the cabinet with the snacks, placed the key on the right spot, and the door popped open.

They looked at each other and made a single, identical clicking sound. A sound of triumph.

I just stood in the doorway. My heart was pounding. It wasn’t about the snacks. It was the coordination. The silent, perfect execution.

Daniel walked in right then. He saw the open cabinet, the broom on the floor, and the boys each holding a bag of crackers.

“What in the world?” he said.

I just pointed to my phone, which had been recording on the counter. “Just watch,” I whispered.

We sat together that night and I played the video. Daniel’s skepticism melted away, replaced by the same hollow-stomach feeling I’d had for weeks.

He watched it three times. The third time, he just shook his head. “Okay,” he said, his voice quiet. “This isn’t twin talk.”

Our pediatrician was kind but useless. He checked their ears, their throats, and their reflexes.

“They’re perfectly healthy boys, Sarah,” he said, handing me a lollipop for each of them. “Some twins just have a very strong bond.”

He gave us a referral to a child development specialist. She was even less helpful. She ran some tests and told us they were “exceptionally bright” but “socially atypical.”

She suggested speech therapy. I almost laughed. They didn’t have a speech problem. They had a speech surplus. They just weren’t sharing it with us.

I spent my nights on the internet, falling down rabbit holes of linguistic forums and developmental psychology papers. Most of it was useless.

Then I found him. Dr. Aris Thorne.

He was a retired linguistics professor from a big university. His specialty was obscure: cryptophasia, the academic term for twin languages.

Most articles dismissed it as simple babble with assigned meaning. But Dr. Thorne had a different theory. He believed that, in very rare cases, twins could develop a true, structurally complex language.

I found an old email address and wrote to him. I poured everything out. The clicks, the gestures, the broomstick heist. I attached a few of the audio files I had collected.

I didn’t expect a reply. I just needed to tell someone who might not think I was crazy.

He replied in under an hour.

His email was short. “Mrs. Miller, I believe I need to meet your sons. I can be in town on Friday.”

Dr. Thorne was not what I expected. He was a small, bird-like man with a cascade of white hair and eyes that sparkled with an almost manic curiosity.

He didn’t talk to me or Daniel at first. He just sat on the floor of the playroom and watched the boys. He didn’t try to engage them. He just observed, a small, quiet man in a rumpled tweed jacket.

Leo and Evan ignored him completely. They chattered away in their secret tongue, building a city of blocks.

After an hour, Dr. Thorne turned to us. His eyes were wide.

“It’s remarkable,” he whispered, as if he were in a sacred library. “It’s not just a language. It’s an artifact.”

He explained it to us in simple terms. He said he believed what the boys were speaking was a kind of “cradle tongue.” A proto-language.

He theorized it was a deeply ancient form of communication, hardwired into our DNA from the dawn of humanity. A language that predated spoken words.

“Normally, it’s overwritten by the language a baby learns from its parents,” he said, his voice full of wonder. “But in some twins, in the silent, isolated world of the womb, that bond is so intense that this ancient tongue is activated. It takes root.”

He had seen fragments of it before. A few shared gestures. A handful of unique sounds between siblings.

“But this,” he said, looking at Leo and Evan, “I have never seen a dialect this complete. It has grammar. It has syntax. It is as real as English or French.”

It wasn’t alien. It was human. Incredibly, anciently human.

The relief I felt was a physical thing. I wasn’t crazy. My sons weren’t strangers. They were just… old souls.

The university where Dr. Thorne had worked became very interested. They offered to fund a full study. It meant brain scans, observation rooms with one-way mirrors, and a team of researchers.

Daniel was excited. He saw it as a chance to understand, to contribute to science. “Imagine what they could learn from our boys, Sarah,” he’d say.

But I was scared. The boys were already retreating. Their English vocabulary, which had been small but growing, had stalled. They preferred their own world.

I felt like their language was a bubble, and I was on the outside, my hands pressed against the surface, watching them drift further away.

The study began. Twice a week, we would go to the university. The boys didn’t seem to mind. To them, it was just a new playroom with weird flashing lights sometimes.

But I hated it. I hated watching them through the glass, a panel of serious-faced academics taking notes. My sons were not a thesis. They were my children.

Then the story leaked. A local news blog ran a piece: “The Clicker Twins: Do These Local Toddlers Have a Secret Language?”

Our phone started ringing. Reporters showed up at our house. People would stop me in the grocery store. It was a nightmare.

We became “that family.” The family with the weird kids.

The bubble around my sons grew thicker. They stopped speaking English altogether. Even simple words like “mama” and “dada” vanished, replaced by their clicks and hums.

One evening, I was trying to read them a bedtime story. They weren’t listening. They were having a quiet, rapid-fire conversation across my lap.

I felt a surge of desperation. “Please,” I said, my voice breaking. “Can you just look at Mama? Just for a minute?”

They didn’t hear me. Or they didn’t want to.

That night, I told Daniel I wanted to pull them from the study. We had a huge fight. He accused me of being emotional, of standing in the way of progress.

“Progress for who, Daniel?” I yelled. “For science? What about for Leo and Evan? I’m losing them!”

I felt utterly alone. I was their mother, the one person who was supposed to understand them, and I couldn’t even ask them if they were hungry.

I started spending every waking moment I could with the recordings. I wasn’t a spy anymore. I was a student.

I imported the audio into a program on my computer. I isolated sounds. I watched the videos frame by frame, linking gestures to noises.

I made flashcards. A high-pitched triplet of clicks seemed to mean “up” or “high.” A low hum from Evan often meant “no” or “stop.” A quick flick of the wrist was “give me.”

It was a slow, grueling process. I was trying to learn a language with no teacher, no textbook, no Rosetta Stone.

One night, I was woken by a whimper from their room. I went in and found Leo thrashing in his crib, caught in a nightmare.

He was crying, but not in a normal way. It was a series of panicked, desperate clicks. A sound I had never heard before.

My heart ached for him. I picked him up and held him close, rocking him, shushing him in English. It didn’t work. He was still lost in his dream.

Then, without thinking, I did something else.

I remembered a sound from the recordings. A soft, two-note hum that Evan often made when Leo was upset about a toy. A sound that always seemed to calm the situation.

I put my lips close to Leo’s ear and I made the sound. It felt awkward and alien in my own throat. A soft, vibrating “mm-hmm.”

Leo stopped thrashing.

The frantic clicking subsided. He went still in my arms. He let out a tiny, sleepy sigh and nestled his head into my shoulder.

He understood me.

I stood there in the dark, tears streaming down my face. It wasn’t a wall between us. It was a door. And I had just found the handle.

The next day, I went to the university. I didn’t talk to the administrators. I went straight to Dr. Thorne.

I told him I was pulling the boys from the formal study. But I made him a counteroffer.

“I want to learn their language,” I said. “And I want you to help me. Not as a researcher studying a subject. As a linguist helping a mother talk to her sons.”

Dr. Thorne looked at me for a long moment. I saw a flicker of something in his eyes. It wasn’t just scientific curiosity. It was wonder.

“A mother’s bond,” he murmured. “It’s the one variable I could never account for. Of course.”

We started a new kind of study. Just the three of us, in our living room. Dr. Thorne would help me analyze the structure, and I would provide the context he was missing.

He showed me how to recognize nouns and verbs. I showed him that a certain click wasn’t a word, but a sound of affection Leo only made when he was hugging his favorite stuffed bear.

We were breaking the code together.

Progress was slow, but it was real. I learned “water.” I learned “more.” I learned the gesture for “sleepy.”

The first true breakthrough was incredible. I was cutting up an apple for their snack. Evan toddled over and made a series of clicks, pointing at a bird on the branch outside our window.

My old response would have been, “Oh, a birdie!”

But now, I listened. I recognized the pattern. It wasn’t just a sound. It was a sentence.

With Dr. Thorne’s help, I pieced it together. The clicks, the pitch, the gesture. He was asking a question. A real, complex question.

“That bird,” he was saying. “It flies. Why can’t we fly?”

I looked at Dr. Thorne. He was beaming.

I knelt down in front of my two-year-old son. I didn’t have the words in his language to explain aerodynamics. But I had learned a few things.

I made the sound for “bird.” Then I made the clicking sound for “up.” I pointed to Evan and made the gesture for “strong legs.” Then I made a little hopping motion. A new word. My word.

He understood. His eyes lit up with a brilliant flash of comprehension. He let out a happy chirp, then hopped once on his sturdy little legs.

Leo came over and chirped too. We were talking. All of us.

We taught them English, too. But we did it by building a bridge from their language. “This,” I’d say, holding the apple and making their clicking sound for it, “is also called ‘apple’.”

They started to learn. The bubble didn’t pop. It expanded to include us.

Years have passed. Leo and Evan are nine now. They are bright, funny, wonderful boys who chatter away in English with their friends at school.

But when they are home, just with us, they still use their cradle tongue.

It’s their language of comfort. Their language of secrets. The language they use when they talk about their dreams or their fears.

I’m not fluent. I never will be. But I know enough. I know the sound for “I love you.” I know the gesture for “tell me a story.”

I know how to listen.

I used to think that my sons were speaking a language that shut me out. But I was wrong. It wasn’t a barrier. It was an invitation.

Love isn’t about demanding that others speak your language. It’s about being willing to learn theirs, no matter how strange or difficult it seems. It’s about finding that door and having the courage to turn the handle.

Their language didn’t take my sons away from me. It brought me closer to them than I ever could have imagined, into a world that was theirs, and that they, in time, chose to share with me.