My grandmother was 94 years old and fading fast. The hospice nurse said we had days, maybe hours. I held her papery hand and leaned in close.

“Nana, please,” I whispered. “The pierogi recipe. The one you promised me.”

She squeezed my fingers. Hard. Harder than a dying woman should be able to.

“Top shelf,” she rasped. “Kitchen. The tin box behind the flour.”

I drove to her house that night. The kitchen still smelled like her – onions and butter and decades of Sunday dinners. I climbed on the step stool, reached behind the five-pound bag of King Arthur, and pulled down a rusted green tin.

I pried it open expecting an index card in her shaky cursive.

There was no recipe.

Inside was a birth certificate. My mother’s birth certificate. Except the name on it wasn’t my mother’s name. And the father listed wasn’t my grandfather.

It was a man named Terrence Wojcik. I’d never heard that name in my life.

Underneath the certificate was a stack of letters, rubber-banded together, addressed to my grandmother from a return address in Scranton. The postmarks spanned 40 years. The last one was dated three weeks ago.

Three weeks ago. Someone was still writing to her.

I opened the most recent letter. The handwriting was neat, deliberate, nothing like a 90-year-old’s.

It read: “Dolores – She’s asking questions now. The girl looks just like him. I can’t keep doing this. Either you tell your family, or I will. You have until Christmas.”

Christmas was four days away.

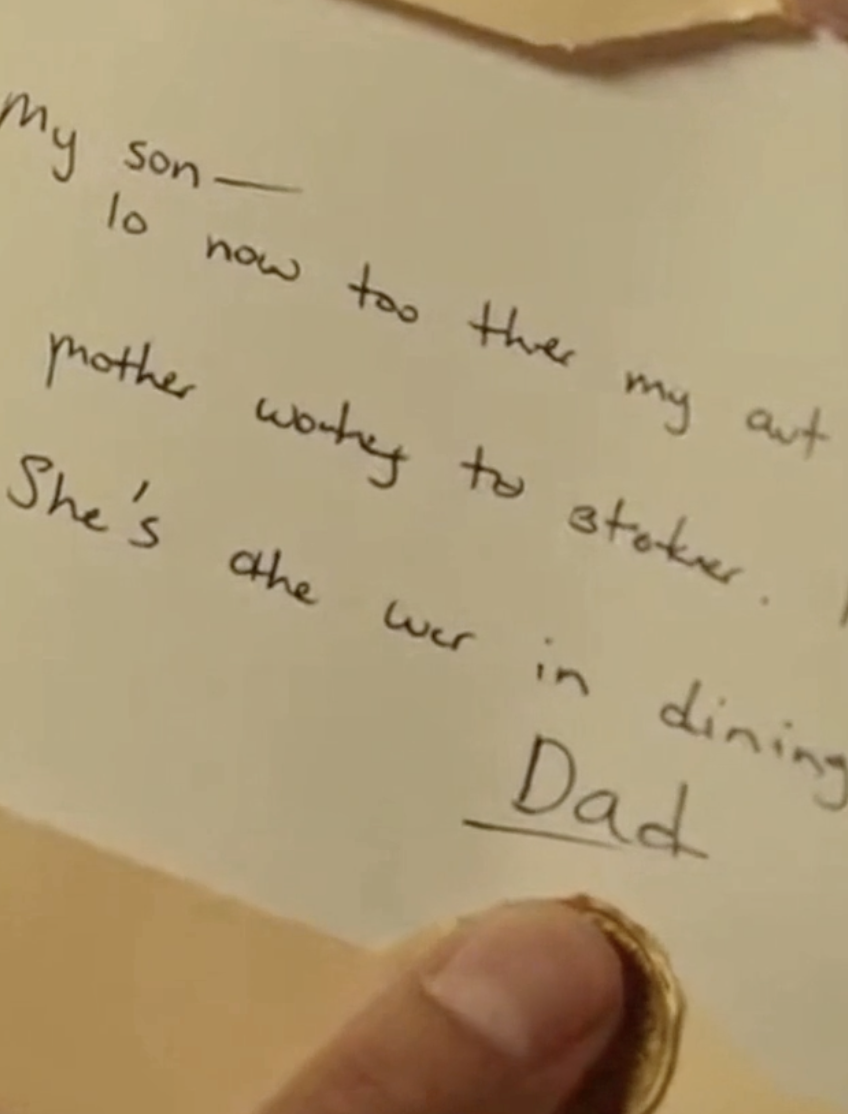

My hands were shaking. I flipped the letter over. On the back, in my grandmother’s handwriting – fresh ink, no tremor – were two words:

“Forgive me.”

I called my mother. She picked up on the first ring, like she’d been waiting.

“Mom,” I said. “Who is Terrence Wojcik?”

Silence. Ten seconds. Twenty.

Then my mother said something that knocked the air out of my lungs.

“How did you find out? She swore she burned everything.”

I looked back into the tin. There was one more thing at the bottom I hadn’t noticed. A photograph, black and white, creased down the middle.

Two babies. Not one. Two.

I turned it over. On the back, in faded pencil: “Dolores & Diane – born March 3, 1961.”

My mother was born March 3, 1961. She was an only child.

I picked up the phone again. “Mom. Who is Diane?”

My mother started crying. Not sad crying. The kind of crying that sounds like something caged finally breaking free.

“She’s not gone,” my mother choked out. “She lives on your street. You see her every single day. She’s your…”

The word hung in the air, unspoken but deafening. My aunt.

“Who?” I managed to ask, my own voice a stranger’s. “Mom, who is it?”

“Mrs. Gable,” she whispered. “From two doors down. The one with the prize-winning roses.”

Mrs. Gable. A quiet widow who always gave me a small, sad smile when she collected her mail. A woman I’d known my entire life as a peripheral figure, a piece of the neighborhood scenery.

My legs gave out and I slid down the kitchen cabinets to the linoleum floor. The floor that Nana had scrubbed on her hands and knees for fifty years.

“I don’t understand,” I said, the rusted tin cold against my leg. “How? Why?”

“It was a different time,” my mother said, her voice steadier now, as if a great weight had been lifted. “Nana was young, and she was in love with Terrence. He was a coal miner from Scranton. He had a laugh that could shake a room.”

She told me the story in fragments, pieces of a puzzle I never knew existed. Terrence wasn’t married. He was just poor. Dirt poor. And when Nana found out she was pregnant, they were overjoyed but terrified.

Then the doctor told them it was twins.

Two mouths to feed. Two bodies to clothe. Terrence worked double shifts, but it was never going to be enough.

That’s when Stanley came into the picture. My grandfather. Or the man I had always called my grandfather. He’d loved Nana for years. He was older, established, owned a small grocery store.

He made her an offer. He would marry her, give her a good life, and raise her child as his own.

But only one.

He said he couldn’t bear the town gossip, the shame of taking on another man’s twins. He would claim one, but the other had to disappear.

My mother’s breath hitched. “Nana had to choose. Can you imagine? Having to choose between your own children?”

She chose my mother. Diane was given up for a closed adoption to a family who couldn’t have children of their own. Dolores and Terrence said a tearful goodbye, and he went back to Scranton, promising to write.

And he did. For forty years, he wrote letters to her, sending them to a post office box she kept secret. He never married. He just wanted to know that his other daughter was okay.

“Grandpa Stanley never knew about the letters,” my mom continued. “He made Nana swear to never speak of Diane or Terrence again. He raised me as his, and he was a good father. But it was a secret that ate at Nana her whole life.”

I looked at the birth certificate again. It listed my mother’s original name, Helen. But the name in the picture was Dolores. “Mom, the picture says Dolores and Diane.”

A soft sigh on the other end of the line. “Nana named you after me. And she named me after herself.”

It was a small act of defiance. A way to keep her lost daughter’s name alive in the family, hidden in plain sight, just like the woman herself.

“How long have you known?” I asked.

“About five years,” she admitted. “Diane found me. She hired a private investigator after her adoptive parents passed away. She just wanted to see the woman who gave her life.”

My mind spun. For five years, my mother had known she had a sister. A sister living two doors down from me.

“She came to Nana’s house,” my mother said. “It was the first time they’d seen each other in over fifty years. Nana almost collapsed. She begged Diane not to tell anyone, not while Stanley was still alive. She was so afraid of him.”

So Diane agreed. She kept the secret. But she wanted to be close. A few years later, when the house on my street went up for sale, she bought it. Just to be near the family she could never claim. Just to watch her niece grow up from a distance.

That explained the smiles. They weren’t just polite neighborly gestures. They were looks of longing.

“And the letters?” I asked, picking up the most recent one. “Who is writing them now?”

“Terrence passed away last year,” my mom said sadly. “He left everything to a nephew, a man named Arthur. He must have found the box of Nana’s replies. I guess he felt his uncle’s wish to connect the family was a promise he had to keep.”

Arthur. He was the one pushing. He was the one who saw me, his newfound cousin, and saw his uncle’s face.

I hung up the phone, my world tilted on its axis. The smell of onions and butter in the kitchen suddenly felt like a lie. Nana’s famous pierogi. The taste of my childhood.

Was that a lie, too?

I spent the next day in a fog, watching Mrs. Gable—Diane—from my living room window. I saw her meticulously pruning her rose bushes, her movements precise and gentle. I saw her bring in her groceries. I saw her sit on her porch swing, staring at nothing, for almost an hour.

I was watching a stranger, and I was watching my family.

That evening, I did the only thing that made sense. I made a batch of Nana’s pierogi. My hands moved on autopilot, pinching the dough, filling it with the cheese and potato mixture. They felt clumsy. The recipe felt hollow.

I packed them in a container, still warm, and walked the two doors down to her house. My heart was a frantic drum against my ribs. What do you say to the aunt you never knew you had?

I rang the doorbell.

She opened it, a surprised but gentle look on her face. Her eyes were my mother’s eyes. They were Nana’s eyes. They were my eyes.

“Clara,” she said. Her voice was soft, like rustling leaves. “Is everything alright?”

“I, um,” I started, my voice failing me. I held out the container. “I brought you some pierogi. My Nana’s recipe.”

A shadow passed over her face, a flicker of a pain so deep it was ancient. She took the container, her fingers brushing mine. Her hands were a gardener’s hands, strong and flecked with soil.

“Thank you,” she said. “That’s very kind.”

She started to close the door, the polite dismissal of a neighbor.

“I found a box,” I blurted out. “In her kitchen. Behind the flour.”

Diane froze. Her knuckles went white on the doorknob. She didn’t speak, but her eyes asked the question.

“I know,” I whispered. “I know who you are.”

The tears that filled her eyes weren’t of shock or fear. They were of relief. She opened the door wider and stepped aside.

Her house was a mirror image of mine, but it felt different. It was quiet, meticulously clean, and filled with books. On the mantle, there were no family photos. Just one small, silver frame.

I walked closer. It was a picture of a handsome young man with a wide, easy smile.

“That’s him,” Diane said from behind me. “That’s our father. Terrence.”

We sat in her kitchen for hours. She told me about her life, her adoptive parents who were kind but always distant. She told me about the feeling of being untethered, of always searching for a face that looked like hers in a crowd.

She told me about the day she met our grandmother. “She looked at me like I was a ghost,” Diane said, her voice trembling. “She touched my face, my hair. And then she begged me to go away.”

My heart broke for her. For the life she’d lived on the outside, looking in.

“She was just so scared,” I tried to explain.

“I know,” Diane said, nodding. “Fear makes people do terrible things. It makes them build walls where there should be bridges.”

Then she smiled, a real, genuine smile that reached those familiar eyes. “Your pierogi are good,” she said, nodding at the container. “But they’re not quite right.”

She stood up and went to a small wooden recipe box on her counter. She pulled out a yellowed, grease-stained index card. The handwriting on it was a beautiful, strong cursive.

“Terrence sent this to me, years ago,” she said, handing it to me. “He said his mother taught him how to make them. He said it was our family’s recipe. Our real family.”

I looked at the card. The ingredients were mostly the same, but there were a few key differences. A pinch of nutmeg in the filling. A bit of sour cream in the dough. Small details that would change everything.

The secret ingredient wasn’t an ingredient at all. It was the truth.

The next day, my mother and I brought Diane to the hospice. We walked in together, the three of us.

Nana was awake, but barely. Her eyes were closed.

My mom leaned in first. “Mom,” she whispered. “I brought someone to see you.”

Nana’s eyes fluttered open. She looked past my mother, past me, and saw Diane standing in the doorway.

A single tear rolled down her wrinkled cheek. She lifted a trembling hand, not just to my mother, but into the space between them.

Diane moved forward and took her hand. My mother took the other. Two daughters, holding their mother’s hands for the first and last time.

No words were spoken. None were needed. The forgiveness my grandmother had written on the back of the letter was finally granted, not in words, but in the simple act of being there.

Nana passed away peacefully that night.

A few days later, a man knocked on my door. He was in his late forties, with kind eyes and the same easy smile as the man in the silver frame.

“Clara?” he asked. “I’m Arthur Wojcik. I think we’re cousins.”

It was the letter writer. He wasn’t a threat. He was just a man trying to honor his uncle’s last wish: for his family to be whole. He told us stories about Terrence, about his booming laugh and his lifelong heartbreak. He filled in the missing pieces of a man we never knew.

Christmas came, just four days later, just as the letter had promised. But it wasn’t a deadline. It was a beginning.

We gathered in Nana’s house, which the three of us were now clearing out together. We decided to cook one last meal there, for old time’s sake.

My aunt Diane brought the yellowed index card. My mother brought the potatoes and cheese. I brought the flour and the sour cream.

In the kitchen that had held so many secrets, we made the real family recipe. We laughed as we rolled the dough. We shared stories. Diane told us about her travels. My mother talked about her childhood. I talked about my dreams for the future.

The air wasn’t thick with secrets anymore. It was light and warm, filled with the comforting smell of onions and butter and nutmeg.

A family isn’t just about the stories we tell; it’s also about the truths we’re brave enough to face. Sometimes the most treasured family recipe isn’t about ingredients written on a card, but about the love and forgiveness that finally brings everyone to the same table. We had lost a grandmother, but we had found a family. And that was the greatest inheritance of all.