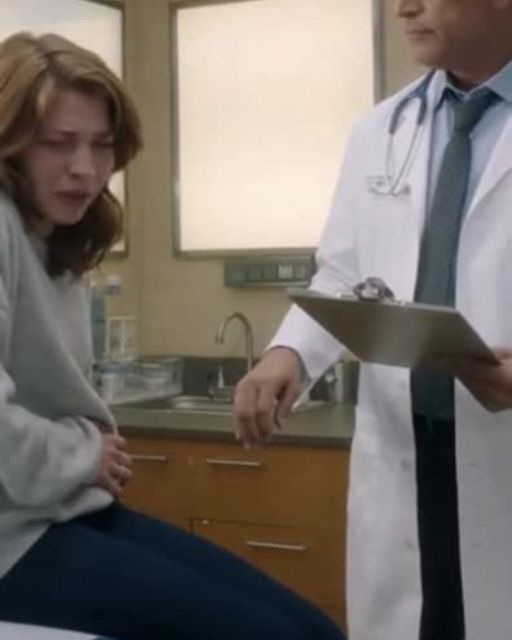

He didn’t even look up from his chart. “Vera, at your age, some aches and pains are normal. I think you’re being a little overdramatic.”

My husband, Robert, sitting in the corner, nodded like a bobblehead. For six months, I had been telling them both about the sharp, grinding pain in my hip. It wasn’t just an ache. It was a nine-out-of-ten pain that made my vision swim. But Dr. Albright had decided it was just anxiety.

I felt that familiar heat rise in my cheeks. The kind of shame that makes you feel small and stupid. “It’s not normal,” I said, my voice shaking a little. “I want an X-ray.”

He let out an exaggerated sigh. The kind that says you’re wasting my valuable time. But he scribbled the order, and I went. I felt defeated, sure he’d be proven right.

An hour later, I was back in his office. He strode in, all confidence, and clicked his mouse to pull up my images on the big screen.

The silence was deafening.

He stopped talking. He stopped typing. He just stared. Then he leaned closer to the monitor, so close his nose almost touched the screen. His whole posture changed. He went pale. I mean, sheet-white.

He slowly backed away from the monitor, never taking his eyes off it. Then he looked at me, his voice a completely different tone. It was just a whisper.

“How long… how long has that been in there?”

I looked from his terrified face to the screen. Robert got up and walked over, peering at the black and white image of my own bones.

There, nestled against my hip bone, was a clear, sharp object. It was undeniably metal, dense and white on the film. It was small, maybe an inch long, but it had a distinct, impossible shape.

It looked like a key.

“What is that?” Robert asked, his voice suddenly sharp with concern, his previous dismissal forgotten.

Dr. Albright just shook his head, running a hand through his perfectly styled hair, messing it up. He looked at me as if I were a ghost. “Vera, I… I have no idea. Have you had surgery before? An accident?”

I shook my head, my mind a complete blank. I’d broken my arm as a kid, that was it. I’d never had stitches anywhere near my hip.

“It can’t be,” I mumbled, staring at the alien object inside of me. “It just can’t.”

Dr. Albright, to his credit, snapped into action. His arrogance was gone, replaced by a frantic, focused energy. He was on the phone in seconds, calling a colleague, an orthopedic surgeon, speaking in hushed, urgent tones.

Robert put his hand on my shoulder, but it felt heavy and strange. He was looking at the X-ray, then at me, then back again. I could see the wheels turning in his head, the confusion warring with a new, dawning fear.

The drive home was silent. The normal chatter about groceries and what to watch on television felt absurd. We had a key in my hip. A key.

That night, I couldn’t sleep. I lay in bed, feeling the dull, grinding ache and imagining that little piece of metal. Where did it come from? How could I have an entire object inside my body and not know it?

I tried to sift through my memories, panning for any little nugget of a forgotten trauma. I remembered falling out of a tree when I was seven. I remembered a bad bike crash at twelve. But none of it felt big enough, monumental enough, to explain a key.

Robert was quiet too. He kept looking at me with an expression I couldn’t read. It wasn’t just concern. It was something else, something deeper and more troubled.

The next few days were a blur of appointments. We saw the surgeon, Dr. Miller, a woman with kind eyes and a no-nonsense attitude. She showed us a more detailed 3D scan.

The object was even clearer now. It was an old-fashioned skeleton key, the kind you’d see in a storybook. It was ornate, with a rounded top. The metal was lodged right against the bone, and over the years, my own body had tried to deal with it, encasing it in tissue.

“I’ve seen a lot of things left in people,” Dr. Miller said, her voice gentle. “Surgical sponges, screws, even a bullet or two. But I have never seen a key.”

She explained that the pain I was feeling was because the key had likely shifted slightly, or the scar tissue around it had started to irritate a nerve. Leaving it in wasn’t an option anymore. It had to come out.

The surgery was scheduled for the following week. In the meantime, the mystery of the key consumed our lives. We called my parents, my older brother. No one could remember any incident.

“You were always a tough kid, Vera,” my dad said over the phone. “Always bouncing back. But I’d remember something like this.”

Robert grew more and more distant. He’d sit in his armchair for hours, just staring into space. When I’d ask him what was wrong, he’d just shake his head. “Just worried about the surgery, hon.”

But I knew it was more than that. Something had shifted in him since he saw that X-ray. The certainty he always wore like a comfortable coat was gone.

One evening, two days before the surgery, I was looking through old photo albums, hoping for a clue. I found a picture of myself at a family picnic when I was about six years old. I had a big scrape on my knee and a bandage on my elbow. I looked like a happy, clumsy kid.

I showed it to Robert. “See? I was always getting banged up. It must have happened then.”

He took the photo from my hand and stared at it. His knuckles were white. He wasn’t looking at me. He was looking at the background, at the blurry figures of other families at the park.

“Robert? What is it?”

He didn’t answer. He just got up and walked out of the room. I heard the back door slide open and shut.

I found him on the patio, looking up at the stars. His shoulders were shaking. I had seen my husband cry exactly twice in our thirty years of marriage: when his father passed, and when our daughter was born. This was different. This was a deep, soul-shaking sorrow.

I sat down next to him. “Talk to me,” I said softly.

He took a long, ragged breath. “The park in that photo,” he started, his voice thick. “That’s Green Lake Park, isn’t it?”

I nodded. “I think so. My aunt lived near there.”

“My family used to go there too,” he said, his voice barely a whisper. “We went to a church picnic there one summer. I was seven.”

He finally turned to look at me, and his eyes were filled with a kind of horror I had never seen before.

“Vera, there was a girl. I didn’t know her name. She had pigtails, just like in that photo. We were playing pirates down by the creek.”

My blood went cold. A flicker of a memory, so faint it was like smoke, appeared in my mind. The smell of wet leaves. The sound of running water.

“I had this little treasure chest,” he continued, the words tumbling out now. “A toy. It had a little brass key. It was my greatest treasure.”

He choked on a sob. “We were running and climbing on the rocks. I was chasing her. I was holding the key in my hand, pretending it was a pirate’s hook or something stupid like that. She slipped.”

He buried his face in his hands. “She fell. She fell right on my hand. Right on the key. She started screaming, a sound I’ll never forget. I saw blood. I panicked. I thought I had killed her.”

The pieces slammed into place in my mind with a physical force. The grinding pain in my hip. The key. The boy with the dark hair and the scraped knees from my own hazy, fragmented memory.

“I ran, Vera,” he whispered, his whole body trembling. “I just ran. I never told anyone. I pushed it down so deep, so far down, I think… I think I actually made myself forget it was real. It just became a nightmare I sometimes had.”

I sat there, frozen. The man I had loved for three decades, the man who had dismissed my pain, was the one who had caused it.

He looked up at me, his face a mess of tears and shame. “When I saw that X-ray… the shape of it… it was like a ghost story coming to life. And when you told me for months that you were in pain, I didn’t listen. I told you it was nothing. I think… I think a part of me knew. A part of me didn’t want it to be real, so I told you it wasn’t. It was easier to believe you were being dramatic than to believe I had done something so horrible.”

The anger I should have felt simply wasn’t there. All I could see was the scared seven-year-old boy still living inside my husband. A boy who had carried a secret so heavy it had nearly crushed him. And I saw the man who was so terrified of his own past that he couldn’t see my present.

I reached out and took his hand. It was cold and damp. “You were a child, Robert,” I said, my own voice unsteady. “It was an accident.”

The surgery was the next morning. Robert never left my side. He held my hand until they wheeled me into the operating room, his eyes pleading for a forgiveness I had already given him.

When I woke up, the first thing I felt was… nothing. The grinding pain, the constant companion of the last year, was gone. There was surgical soreness, yes, but the deep, internal agony had vanished.

Robert was there, asleep in the chair next to my bed, his face etched with worry even in his dreams.

A few hours later, Dr. Miller came in. She was holding a small, sterile jar. Inside, sitting on a piece of white gauze, was a small, tarnished brass key. It was exactly as we’d seen it on the scans.

“It came out clean,” she said with a smile. “You’re going to feel a world of difference.”

Dr. Albright came by later. He looked humbled, and profoundly sorry. “Vera, I want to apologize. I failed you as a doctor. I should have listened. I will never make that mistake again.” He told me he’d made a substantial donation to a foundation for chronic pain research in my name.

Recovery was slow, but every day was better than the last. Robert was a different man. The wall he’d built around himself had crumbled. He was attentive, gentle, and he listened. He truly listened, not just with his ears, but with his whole heart.

One afternoon, about a month after I came home, he came into the living room holding the little brass key, now cleaned and polished. He also held a small, dusty wooden box.

“My mom sent it,” he said. “It was in her attic. It’s the treasure chest.”

He handed it to me. I opened the lid. Inside, there was a robin’s eggshell, a smooth, grey stone, and a single, faded photograph.

It was of two children, sitting on a rock by a creek. A little girl with pigtails and a bright smile, and a little boy with dark, messy hair, holding a small wooden box. It was us. We had been in each other’s lives, a secret chapter of our story, long before we ever knew it.

Holding that key, I realized it had been more than just a source of pain. It was a catalyst. Its discovery hadn’t just healed a physical wound I’d carried for decades. It had unlocked a hidden truth in my marriage, forcing us to confront a memory that had haunted us both in different ways.

My pain was real, even when no one else could see it. It was a messenger, trying to tell me a story I had long forgotten. The lesson wasn’t just for the doctor who dismissed me, or the husband who couldn’t hear me. It was for me, too. We must learn to trust the language of our own bodies, for they hold the truths and the histories that our minds sometimes choose to forget. And in listening, truly listening, to ourselves and to each other, we find the key not to pain, but to a healing we never thought possible.