It was 1862, the year America was tearing itself in two, and George Custer was still more ambition than legend. Young, sharp-eyed, and already rising fast in the ranks, he carried a hunger for greatness—and a heart not yet hardened by war.

He’d seen the worst of it by then. Soldiers broken, bodies buried in shallow graves, towns reduced to ash. But nothing hit him like that cold, gray morning when they reached a Confederate prison camp tucked deep in the woods.

The prisoners looked like shadows of men—Union, Confederate, and a few civilians too weak to stand. But one man stood apart. Shackled. Barefoot. Eyes low, but spine straight. A Black man. A slave.

“What’s his name?” Custer asked a guard.

“Joseph,” the man muttered. “Belongs to a plantation nearby. Got caught up in the mess.”

But Joseph didn’t look like he belonged to anyone.

Custer dismounted, something in his chest tightening. Joseph didn’t flinch, didn’t beg. Just stared back, steady.

“You don’t deserve to be here,” Custer said quietly.

Joseph didn’t answer. He didn’t need to.

“I’m getting you out,” Custer said. And that was that.

No permission. No orders. Just a young lieutenant making a choice.

He marched up to the guards and claimed Joseph as his own. Maybe it was the uniform. Maybe it was the fire in his voice. They didn’t stop him.

Moments later, the chains fell. Joseph stepped forward, still cautious—but free.

They rode out of that place together, not as master and servant, not as officer and rescued, but as two men in a country at war with itself. And though Custer didn’t know what came next, he knew one thing for certain—this moment mattered.

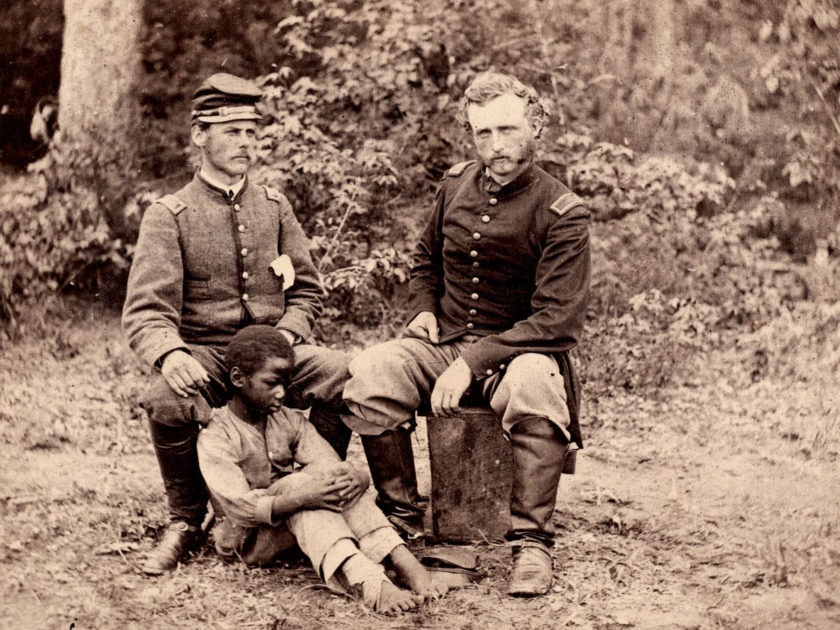

Later, someone took a photo of them. Custer in uniform. Joseph beside him, cloak draped over his shoulders. Two men who should’ve never crossed paths. But they did.

And in a war full of darkness, this was one moment of light.

Joseph didn’t speak much during the ride back. But when he did, his words landed like truth dropped into still water.

“You didn’t have to do that,” he said, eyes watching the trees blur past.

Custer kept his hands steady on the reins. “No, I didn’t. But sometimes doing nothing costs more.”

They rode until dusk, arriving at the Union camp near a small clearing off the James River. Custer vouched for Joseph’s freedom, pulling every ounce of influence his young rank could offer. Papers were drawn up. A name recorded. Not a slave. Not cargo. A free man.

Joseph was quiet while the officer wrote his name.

He stared at the paper. At the ink. Then slowly, he spelled out each letter: “Joseph Warner.”

Custer tilted his head. “That your name?”

Joseph nodded once. “It is now.”

A week later, Joseph began working with the medical unit—at first, just hauling water and supplies. But within days, the surgeons noticed his calm hands, the way he learned quickly, remembered everything.

“Where’d you pick this up?” one asked.

Joseph shrugged. “Watched a doctor once. On the plantation. When they broke a man’s leg. I paid attention.”

He had a gift. And soon, even Custer had to admit—Joseph saved more lives in one week than any rifleman could.

One night, sitting by the fire, Custer looked over at him. “What’ll you do after all this?”

Joseph didn’t hesitate. “Start something that gives folks like me a way forward. Maybe a school. Or a place to rest.”

Custer nodded. “You will.”

The war pressed on. Bloodier, crueler. Custer was promoted. Joseph stayed near the front, bandaging wounds, comforting the dying. They were never quite friends—but always something deeper than strangers.

Until one night near Culpeper, a Confederate ambush split the camp.

Explosions. Shouts. Smoke. Chaos.

Custer was thrown from his horse, his leg crushed beneath a wagon. He shouted, trying to crawl, blood pouring from his thigh.

And then—Joseph appeared through the haze.

He didn’t hesitate. Lifted Custer, dragged him through mud and fire, bullet grazing his own shoulder. For hours, Joseph stayed by his side, pressing the wound, whispering to keep him awake.

“You’re gonna live, George,” he said.

Custer blinked through tears. “You called me George.”

Joseph smirked. “Well. You called me Joseph.”

It took weeks for Custer to recover. Joseph never left his side.

When Custer was transferred to Washington for recovery, he tried to pull strings—offered Joseph a letter of commendation, even a position in the officer’s circle.

But Joseph shook his head. “You gave me freedom. I need to earn what comes next.”

And so he did.

After the war ended, Joseph headed south—not back to chains, but to purpose. He settled in Richmond, opening a small shelter for former slaves. Taught them how to read. How to write. How to believe they were worth more than what the world told them.

He called it “The Freedman’s Light.”

In 1869, Custer visited, now a full colonel with the weight of politics beginning to press in. He arrived unannounced, stepping into the small brick building and watching children recite lessons with chalk and slate.

Joseph looked up. Smiled.

“Didn’t think you’d come.”

“I said I would.”

They sat on the porch that night, two men older now. Wiser. The bond still unspoken—but strong.

“You changed the course of my life,” Joseph said quietly. “Not just that day at the prison. But because you saw me.”

Custer swallowed. “You earned everything after that. I just gave you space.”

“No,” Joseph said. “You gave me a moment. That’s all it takes sometimes.”

Years passed.

When Custer died at Little Bighorn in 1876, Joseph grieved quietly. Not because he worshipped him. But because the man had chosen right—when it was easier to look away.

Joseph carried on.

By 1880, his school had grown into an academy. By 1890, it was nationally recognized.

On the building’s front wall, carved in stone, were six simple words:

“He saw a man in chains.”