I was admitted to St. Michael’s Hospital last Tuesday with pneumonia. Nothing serious, just needed IV antibiotics and rest.

A nurse came in to take my vitals. She was younger, maybe late thirties, with a tired smile. She avoided eye contact the entire time.

“You’re all set,” she said, turning to leave.

I didn’t think anything of it until she was halfway out the door.

“Wait,” I called. “What’s your name? You’ve been great.”

She froze. Her hand was still on the doorframe.

She didn’t turn around. “It’s just better if you don’t know.”

I felt a chill. “What do you mean?”

She finally looked at me, and I saw fear in her eyes. Real fear.

“Because if you know my name, you’ll ask questions. And if you ask questions, you’ll remember. And if you remember…” She glanced at the chart clipped to the foot of my bed. “You’ll figure out why I’ve been checking on you every hour.”

I reached for the chart. My hands were shaking.

My name was there. Arthur Pendelton. My age. My medical history.

And stapled to the back was a newspaper clipping from 1998. I recognized the photo immediately.

It was me. Twenty-five years younger, with more hair and fewer lines around my eyes.

The headline read: “LOCAL MAN WANTED FOR QUESTIONING IN DISAPPEARANCE OF ELEANOR VANCE – “

The rest was torn. But I didn’t need to read it. I had lived it.

Then I looked at the nurse’s name on her badge, clipped to her scrubs. It was a simple, plastic tag.

The letters stared back at me, a ghost from a past I thought was buried.

S. VANCE.

My breath caught in my throat. It couldn’t be.

“You’re Sarah,” I whispered. The name felt foreign on my tongue after so long.

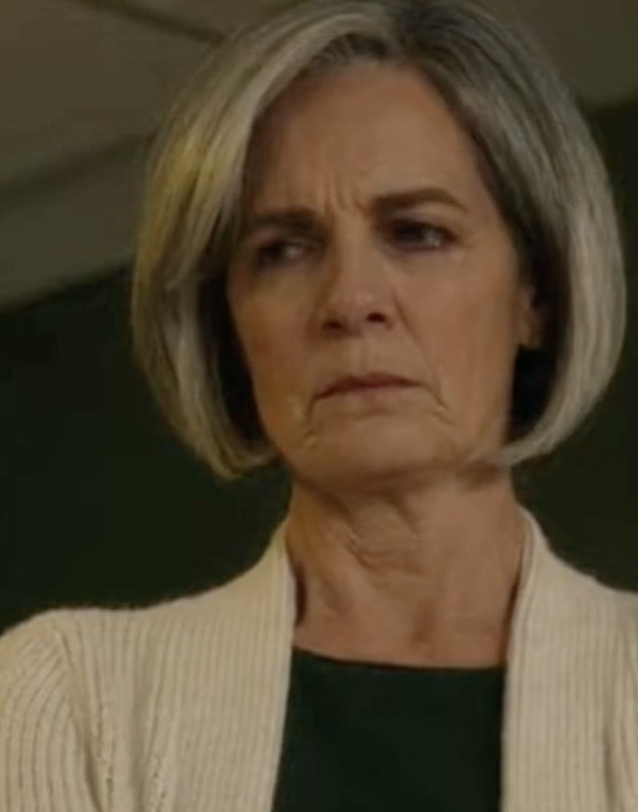

Her face, which had been a mask of professional distance, crumpled. The fear in her eyes was replaced by something harder. Something colder.

“I am,” she said, her voice barely audible. “You took my mother from me.”

The accusation hung in the sterile air of the hospital room, heavier than any illness.

“No,” I said, shaking my head. The word was weak, pathetic even to my own ears. “No, I didn’t.”

“Don’t lie to me,” she hissed, stepping fully back into the room. “I’ve waited my whole life for this. To look you in the eye.”

She gestured to the machines beeping softly around me. “I’m a nurse. I took an oath to do no harm. And every single second I am in this room, I am fighting the urge to break it.”

The raw hatred in her voice was a physical blow.

“Sarah, please,” I begged. “You have to listen to me. It’s not what you think. It was never what it looked like.”

“What it looked like?” she scoffed, a bitter laugh escaping her lips. “It looked like my mother was trying to leave my father. It looked like you were helping her. And then it looked like she vanished, and you were the last person to see her alive.”

“All of that is true,” I admitted, my voice cracking. “But it’s not the whole truth.”

She stood there, arms crossed, a guardian at the gate of a painful history. She wasn’t a nurse anymore. She was a ten-year-old girl who had lost her whole world.

I knew I had to tell her. I had to make her understand.

“Your mother was my friend,” I started. “We worked together at the library. She was the kindest soul I ever met.”

I could see Eleanor in Sarah’s face. The same strong jawline, the same intensity in her eyes.

“She used to talk about you all the time,” I continued. “How you loved to read, how you could build entire worlds with your Lego sets. You were her everything.”

A flicker of something – doubt, pain, a long-lost memory—crossed her face before the mask slammed back down.

“Get to the point,” she said, her voice clipped.

“Your father… Marcus… he was not a good man, Sarah.”

“Don’t you dare talk about my father,” she snapped. “He was a saint. He raised me by himself. He worked two jobs to keep a roof over our heads after what you did.”

I sighed. The story Marcus had spun was a powerful one. Of course she believed it. He was all she had left.

“He was hurting her,” I said softly. “The bruises she tried to cover with long sleeves in the middle of summer. The way she would flinch if someone moved too quickly behind her. I saw it. I couldn’t ignore it.”

“You’re lying,” she whispered, but the conviction was gone from her voice.

“We made a plan,” I said, my mind drifting back a quarter of a century. “I had a cousin in Oregon who agreed to take you both in. A new start. A safe place.”

“I was supposed to pick her up that night. We were going to meet at the old bridge by Miller’s Creek, then we’d come back and get you while your father was on his night shift.”

My throat felt tight. “She never showed up.”

“I waited for hours. I called her house, but there was no answer. Finally, I drove by. All the lights were off. I thought maybe she’d gotten scared and changed her mind.”

“The next day, she was reported missing. And your father told the police I was obsessed with her. That I was a stalker who couldn’t handle rejection. That I probably snapped and… and did something to her.”

Sarah was silent now. Her arms had fallen to her sides. She was just listening.

“The police questioned me for days,” I said, the shame still fresh. “My face was on the news. People in town would cross the street to avoid me. I lost my job. I lost my friends. I lost everything.”

“They never had enough evidence to charge me, but it didn’t matter. In everyone’s eyes, I was guilty. So I left. I moved three states away and started over. I changed my name for a while. I just wanted to forget.”

The room was quiet except for the rhythmic beep of the heart monitor. It was a steady, reassuring sound that was completely at odds with the chaos in my soul.

“If you’re telling the truth,” Sarah said finally, her voice trembling, “then what happened to her?”

“I don’t know,” I confessed, and the not-knowing was the heaviest burden of all. “I’ve gone over that night a million times in my head. The only thing I can think of is that Marcus found out about the plan. That he got home early and stopped her from leaving.”

“No,” she said, shaking her head. “He was at work. I remember. He came home the next morning and he was crying. He told me Mommy had gone away.”

“Are you sure?” I pressed gently. “You were ten years old. Memories can get fuzzy.”

“I am sure,” she insisted. “He was a security guard at the pharmaceutical plant. He had to punch in and out. The police checked his time cards. He had an alibi.”

My heart sank. It was the one detail that had never made sense. The one thing that always led the trail of guilt back to my own front door.

For the next few days, an unspoken truce existed between us. Sarah would come in to do her job. She was professional, efficient, but the cold hatred was gone. It had been replaced by a heavy, uncertain silence.

She’d check my IV, take my temperature, and her eyes would be full of questions she was too afraid to ask. And I saw her looking at me, really looking, as if trying to see a monster and finding only a tired old man.

One afternoon, she came in with my lunch tray.

“I looked you up,” she said, placing the tray on the rolling table. “Arthur Pendelton. You’re a retired schoolteacher. You volunteered at an animal shelter for fifteen years. You have two letters of commendation for your community work.”

She looked at me. “It doesn’t fit. The man in these articles isn’t a killer.”

“I told you, Sarah. I’m not.”

“My father,” she began, then stopped. “He always told me to never speak of her. He said it was too painful. He threw out all of her pictures. It was like he was trying to erase her.”

“Maybe he was trying to erase his guilt,” I suggested.

She flinched, but she didn’t deny it. “There’s something else.”

She reached into her pocket and pulled out her phone. She swiped a few times and then handed it to me. On the screen was a photo of a small, silver locket, shaped like a heart.

“This was my mother’s,” she said. “It was the only thing of hers my father let me keep. He said she left it behind on her dresser.”

My blood ran cold. I knew that locket.

“Can I see it?” I asked, my voice hoarse. “The real thing?”

She hesitated, then nodded. “I’ll bring it tomorrow.”

The next day felt like an eternity. When she finally arrived for her shift, she walked in without a word and placed the cool metal of the locket in my hand.

It was just as I remembered. Tarnished with age, but still beautiful.

“Eleanor was supposed to give this to you,” I said, my thumb tracing the engraved initials on the front. E.V. “She told me about it the week before she disappeared.”

I pressed a tiny, almost invisible clasp on the side. With a soft click, the locket sprang open.

On one side was a faded picture of a smiling little girl with pigtails. It was Sarah.

On the other side, tucked behind the frame, was a tiny, folded piece of paper. My fingers, clumsy with age and emotion, struggled to get it out.

Sarah helped me. We unfolded it together on the bedside table.

It was a bus ticket. A one-way ticket from our small town to Portland, Oregon.

The date stamped on it was the day after she disappeared.

Sarah stared at it, her face pale. “She… she was really leaving.”

“Yes,” I said. “And she was taking you with her.”

“But why would she leave the locket?” Sarah whispered, tears welling in her eyes. “Why would she leave this ticket behind?”

“She didn’t,” I said, a terrible, dawning realization washing over me. “She wouldn’t have. This was her proof, her hope. This was everything.”

We both looked at each other, the same unspoken thought passing between us.

If Eleanor didn’t leave it, someone else did. Someone who wanted it to be found. Someone who wanted to create a story about a woman who simply ran away from her life.

“His alibi,” I said. “The time cards. What if they were faked? What if someone punched in for him?”

“It was a small company back then,” Sarah murmured, her mind clearly racing. “Not a lot of security. Everyone knew everyone.”

A new energy filled the room. After twenty-five years of dead ends and unanswered questions, we finally had a path. A tiny one, but it was there.

Over the next few days, Sarah made some calls. She spoke to old friends of her mother’s, former employees from the plant. She pieced together fragments of a life she was never allowed to know.

She found out her father had a gambling problem. That he was deeply in debt. That he had a reputation for a violent temper, one he hid well behind a charming smile.

Then she found Beatrice. Beatrice had been Eleanor’s best friend. She had moved away shortly after the disappearance, too heartbroken to stay.

Sarah spoke to her on the phone for hours. Beatrice told her things that made her sick. Stories of Marcus’s cruelty, of Eleanor’s fear.

And she told her one more thing.

“Your father had a brother,” Beatrice said. “A real piece of work. Looked just like him. Frank. He worked at the plant, too. Got fired for stealing a few months after your mom… went away.”

The final piece of the puzzle clicked into place.

Sarah was pale when she came to see me that evening. “Frank Vance,” she said. “My uncle. He died in a car accident in 2005. But before he died… he punched the clock for my father that night.”

“He confessed it to a friend,” she continued, reading from a notepad. “Said Marcus paid him five hundred dollars to cover for him for a few hours. Said Marcus told him he just needed to ‘talk some sense’ into Eleanor.”

There it was. The lie that had protected a monster for twenty-five years. The lie that had ruined my life and stolen Sarah’s mother.

The truth was a bitter pill, and Sarah was choking on it. The man who had raised her, the man she had called a saint, was a murderer.

That night, a new patient was admitted to the room across the hall. He was old, frail, and dying of liver failure. He was cantankerous and rude to the staff.

I didn’t pay him much mind, until I heard his voice shouting at a nurse. It was a gravelly, weak voice, but there was a familiar cadence to it. A rhythm I hadn’t heard in decades, but would never forget.

I asked Sarah to check his name on the chart.

“It’s an old man named Joseph Peterson,” she said, dismissing my concern.

But I couldn’t let it go. Later that day, as a nurse was helping him, I saw his arm. And on his forearm was a faded, blurry tattoo.

It was a coiled snake.

Marcus Vance had a coiled snake tattooed on his forearm. He got it when he was in the Navy. Eleanor had hated it.

My heart hammered against my ribs. It was him.

He was here. In the same hospital. Just a few feet away.

I told Sarah. She didn’t believe me at first. It was too much of a coincidence. Too cruel a twist of fate.

But she went into his room under the pretense of checking his vitals. She came out five minutes later, her face as white as her uniform.

“It’s him,” she whispered. “He’s lost weight, his hair is gone… but it’s him. It’s my father.”

He had been living under an assumed name for the last ten years, ever since his gambling debts had finally caught up with him.

The universe, in its strange and mysterious way, had brought us all together under one roof. The accuser, the accused, and the murderer.

Sarah knew what she had to do.

She walked back into that room. I followed, standing in the doorway, my legs feeling weak.

“Dad?” she said.

The old man, Joseph Peterson, turned his head on the pillow. His eyes, cloudy with sickness, widened in recognition. Then, in fear.

“Sarah? What are you doing here?” he rasped.

“My name is Nurse Vance,” she said, her voice shaking but firm. “And I have a question for you. What did you do to my mother?”

He tried to bluster, to deny it. He called her crazy. He said he didn’t know what she was talking about.

But his eyes betrayed him.

Then he saw me, standing in the doorway. The ghost of his greatest lie.

All the fight went out of him. Maybe it was the sickness, or the weight of the years, or the simple shock of being confronted by his two biggest secrets at once.

He broke.

He confessed everything. He had come home early that night and found the packed bags. He saw the bus ticket. He flew into a rage.

He told her she would never take his daughter from him. He hit her. And he didn’t stop.

He buried her in the woods behind the plant that night, in a place no one would ever think to look. He paid his brother to cover for him. He left the locket on the dresser to create a false trail.

He looked at Sarah, and for the first time, I saw a flicker of something that might have been remorse in his hollow eyes.

“I did it for you, pumpkin,” he wheezed. “I couldn’t let her take you away.”

Sarah just stood there, tears streaming down her face, as the man who was supposed to protect her confessed to destroying her life.

He passed away two days later.

Sarah reported everything to the police. With the confession and the evidence from Beatrice, my name was officially cleared. A formal letter of apology was issued by the town council. Twenty-five years too late, but it was something.

They found Eleanor’s remains right where he said they would be. She was given a proper burial, next to her own mother.

My pneumonia cleared up, and I was discharged from the hospital. Sarah was there to see me off.

We stood by the entrance, the cool morning air a welcome change from the stale hospital rooms.

“I’m so sorry, Arthur,” she said, her voice thick with emotion. “For everything. For what I believed. For what I said to you.”

“You have nothing to be sorry for,” I told her, and I meant it. “You were just a little girl who believed her dad. Anyone would have.”

She reached out and, for the first time, took my hand. Her grip was strong.

“Thank you,” she said. “For not giving up on the truth. For giving me my mother back.”

We didn’t say much else. We didn’t need to. In that shared moment, a bond was formed. Not of friendship, not quite family, but something in between. Two survivors of the same shipwreck, finally finding shore.

Life has a funny way of holding on to secrets, tucking them away in dark corners until it decides it’s time for them to see the light. For twenty-five years, I carried the weight of a crime I didn’t commit, while a young woman carried the weight of a mother she thought had abandoned her. We were both prisoners of the same lie. The truth didn’t erase the pain or bring back the years we lost, but it did something just as important. It set us free. It taught me that sometimes, the most profound healing comes not from forgetting the past, but from finally, finally understanding it.