The manager’s voice cut through the clatter of the café.

“We don’t serve your kind here. Get out.”

Every conversation stopped. Every head turned to look at me, at the dirt on my coat and the wear on my boots. I felt the heat of a hundred eyes on my neck.

He was a young guy, sharp suit, sharper smirk. He saw a problem to be scrubbed away, not a person.

“I just want a coffee,” I said, my voice quiet.

That just made him angrier.

He took a step toward me, puffing out his chest. He wanted the whole room to see him solve this. To see him dispose of the trash.

“Are you deaf? I said get out. Now.”

Some people shifted uncomfortably. A few others looked down, suddenly fascinated by the sugar packets on their table. No one said a thing.

I looked at his face. The pure, unvarnished contempt. He wasn’t just doing a job. He was enjoying this.

And in that moment, the entire visit changed.

I didn’t say anything back.

Instead, I reached for the zipper on my torn, filthy jacket. The sound it made in the dead-silent room was like a gunshot.

I pulled the jacket off, letting it drop to the tiled floor in a heap.

Underneath, my suit was pristine. A dark charcoal wool, custom-tailored. On my lapel was a small, almost invisible pin. The company emblem.

I watched the manager’s eyes flicker from my face, to the suit, to the pin.

I watched the smugness on his face curdle. It dissolved into confusion, then into the pale, sickly green of sheer panic. His mouth hung open.

I took out my phone and dialed my head of operations.

“Alan,” I said, my voice perfectly level. “We have a vacancy for a branch manager at the downtown location. Effective immediately.”

Kindness is never an accident.

It’s a decision. And not everyone is qualified to make it.

The silence that followed the phone call was heavier, more profound, than the one before.

The young manager, whose name tag I could now see read ‘STEVEN,’ was ashen. He looked like a statue, frozen in the moment his world had shattered.

His jaw worked, but no sound came out.

I felt a cold satisfaction, but it was quickly replaced by something else. A hollow ache. This wasn’t a victory. It was a failure. A failure of the system I was now in charge of.

My father had started this chain of cafés, “The Daily Grind,” with a simple philosophy. He believed a coffee shop should be a town’s living room, a place for everyone.

He used to say that the price of a cup of coffee bought you a safe, warm place to sit for an hour, no questions asked.

He had passed away two years ago, leaving the entire company to me, his only son, Arthur.

I had spent those two years in boardrooms, looking at spreadsheets and profit margins. I’d been so focused on the numbers that I had lost sight of the soul of the business.

This little experiment, dressing down and visiting my own stores, was supposed to be a check-in. A way to reconnect with my father’s vision.

Instead, it had exposed a rot I hadn’t known was there.

I bent down and picked up the dirty coat from the floor. It was an old army surplus jacket my father had worn when he worked in the garden. It still smelled faintly of soil and his pipe tobacco.

As I held it, a young woman, a barista, rushed forward.

“Sir, I am so sorry,” she whispered, her hands twisting in her apron. “I was going to get you a water. I shouldn’t have waited.”

I looked at her. Her name tag said ‘MARIA.’ There was genuine distress in her eyes. She hadn’t been enjoying the show. She’d been afraid.

“It’s not your fault,” I told her, my voice softer now.

I turned back to Steven. The panic in his eyes was giving way to a desperate, cornered anger.

“Who are you?” he finally managed to choke out.

“My name is Arthur Pendelton,” I said calmly. “My father was Robert Pendelton. He built this place.”

The name landed like a physical blow. Everyone in the café knew the founder’s name. His picture hung on the wall behind the counter, a smiling, kind-eyed man in a simple work shirt.

Steven’s eyes darted to the picture, then back to me. The last bit of color drained from his face.

The front door chimed, and a man in an equally sharp suit hurried in. This was Alan, my head of operations. He was a good man, but he lived in the world of logistics, not people.

He took one look at me, at Steven, at the silent café, and his face set in grim lines.

“Arthur,” he said, a note of reprimand in his tone. “I told you this was a bad idea.”

“On the contrary, Alan,” I replied, folding the old coat over my arm. “It was the best idea I’ve had in years.”

I gestured to Steven. “Please have security escort Mr. Evans off the premises. Have his personal effects sent to him. And cancel his severance.”

A gasp went through the room. It was one thing to be fired. It was another to be treated so brutally. I saw a flicker of doubt in Maria’s eyes.

Steven just stared, his expression now completely blank. He had been erased.

Alan nodded, already on his phone, making the arrangements.

I turned to Maria. “What’s the most popular drink here?”

She blinked, caught off guard. “Uh, the caramel latte, sir.”

“Make me one of those, please,” I said. “And a simple black coffee. And get one for yourself, whatever you like.”

I walked over to a small table in the corner and sat down, the old coat draped over the empty chair beside me.

The customers started murmuring, the spell of silence broken. Some left quickly, others whispered to their companions. They had witnessed a corporate execution.

Maria brought the drinks over on a tray, her hands trembling slightly.

“Thank you, Maria,” I said. “Please, sit for a moment.”

She hesitated, then slid into the chair opposite me.

I pushed the black coffee toward the empty chair where the coat sat. It was a small, sentimental gesture. My father had always drunk his coffee black.

“Tell me about your time here,” I said to her. “How long have you been with The Daily Grind?”

“Five years, sir,” she said quietly. “I started when your father was still around. He hired me himself.”

That caught my attention. “He did?”

She nodded, a small, sad smile touching her lips. “I was a single mom, just moved to the city. No experience. He said he liked the honesty in my eyes. He said he could teach anyone to make coffee, but he couldn’t teach them to be a good person.”

The words hit me hard. That was my father in a nutshell.

“Things have changed since then, haven’t they?” I asked.

She looked down at her cup. “Yes, sir. A lot.”

“How so?”

“It became… colder,” she said, struggling for the right word. “We used to have a ‘pay it forward’ board. People could buy a coffee for someone in need. Mr. Evans… Steven… he took it down. Said it attracted the wrong element.”

The wrong element. Like me, ten minutes ago.

“We used to know all our regulars by name,” she continued. “Now, it’s all about transaction times. How fast we can get people in and out. We’re told not to chat. It hurts our numbers.”

Numbers. The very thing I had been focused on from my glass tower office.

I had been approving these policies. I’d seen the improved efficiency, the increased profits, and I’d signed off on them, thinking I was being a good businessman.

I had been sanding down the soul of my father’s company, one spreadsheet at a time.

“Why didn’t you speak up?” I asked her, my voice gentle. “When he was shouting at me.”

Her eyes welled up. “I have two kids, sir. This job is all I have. Steven… he fires people for small things. For being five minutes late. For giving a friend a free refill. I was scared. I’m ashamed of it, but I was.”

I nodded slowly. It wasn’t her fault. It was mine. I had created an environment where fear grew more easily than kindness.

Alan returned and stood by the table. “It’s done, Arthur. He’s gone.”

“Good,” I said. “Alan, I’d like you to meet Maria. As of right now, she’s the acting branch manager of this location.”

Both Alan and Maria stared at me in shock.

“Sir, I… I don’t know how to be a manager,” Maria stammered.

“My father thought you were a good person,” I said, looking her directly in the eye. “That’s the only qualification that matters. We can teach you the rest.”

I stood up. “Alan, get her set up. Cancel all the policies on transaction times and customer interaction limits for this branch. And put the ‘pay it forward’ board back up. Use wood from an old crate, not some cheap plastic thing. Make it look like it belongs.”

I left the café, leaving a stunned new manager and a bewildered head of operations in my wake.

The next day, I called Steven Evans into my office at corporate headquarters.

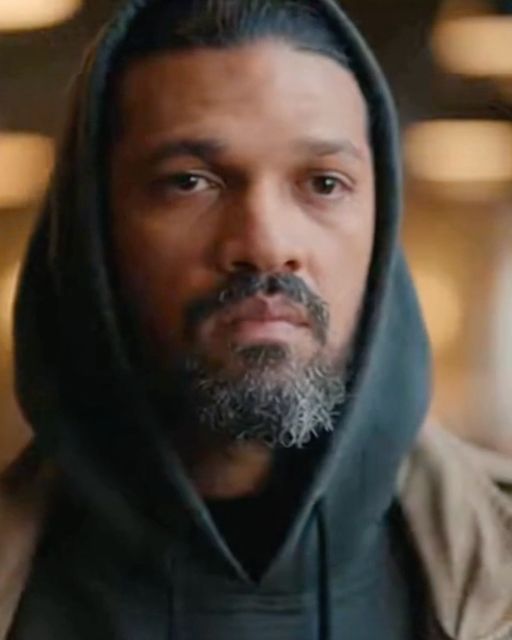

He arrived looking defeated. His sharp suit seemed to hang off him. The smirk was gone, replaced by a deep-set weariness. He looked younger and more fragile without his armor of arrogance.

He sat in the chair opposite my large mahogany desk and didn’t say a word. He just waited for the final blow.

“I’m not going to lecture you,” I began, my voice even. “What you did was wrong. It was a betrayal of everything this company is supposed to stand for.”

He flinched but remained silent.

“I looked into your file,” I continued. “You’ve been with us for three years. Before that, you were at a high-pressure investment firm. Your performance reviews are stellar. Profits at the downtown branch are up 30% since you took over.”

“I did my job,” he mumbled, his voice hoarse.

“You did the job I asked you to do,” I corrected him. “And that’s on me. I rewarded numbers. I incentivized a culture that led to yesterday. So while you are responsible for your actions, I am responsible for the environment that encouraged them.”

He looked up, a flicker of confusion in his eyes. This was not the conversation he was expecting.

“But there’s a difference,” I said, leaning forward. “Between enforcing a policy and enjoying the cruelty of it. I saw your face, Steven. You liked it. You needed to feel powerful by making someone else feel small. Why?”

He looked away, his jaw tightening.

“This is not a trick question,” I said. “I’m not going to re-hire you. That job is gone. But I need to understand.”

For a long moment, he said nothing. The silence in my office was as thick as it had been in the café.

When he finally spoke, his voice was barely a whisper. “My father had a hardware store. A small, independent place. He was like your dad. Knew everyone. Gave people credit when they couldn’t pay. He was a good man.”

He paused, swallowing hard.

“When the big box stores moved in, he couldn’t compete. We lost everything. The store, the house. Everything. We lived in a car for six months.”

He took a shaky breath. “I watched my ‘good man’ of a father get walked all over. People he’d helped for years crossed the street to avoid him. They treated him like he was nothing. Like he was trash.”

The story hung in the air between us.

“I swore I would never be like him,” Steven said, his voice gaining a bitter edge. “I would never be weak. I would never be the one on the ground. I would be the one with the clean suit and the shiny shoes, and I would make sure everyone knew it. I would be the one who decided who belonged and who didn’t.”

He finally looked at me, and for the first time, I saw the scared, hungry kid behind the arrogant manager.

“When I saw you,” he said, his voice cracking, “in that coat… you looked like all the ghosts I’ve been running from my whole life. And I hated you for it.”

It wasn’t an excuse. But it was a reason. A deeply human, deeply broken reason. My father had a saying for people like Steven. “He’s a man walking around with a stone in his shoe. He doesn’t know why he’s angry, he just knows that every step hurts.”

I had a choice to make. I could cast him out, confirm his worst fears about the world—that it’s a brutal place where one mistake gets you thrown on the trash heap.

Or I could do something else.

“As I said, your job as manager is over,” I repeated. “But I have another offer for you.”

He looked at me, wary.

“My father started a foundation. It works with homeless shelters and job placement programs for people who have lost everything. It’s small. Underfunded. I’ve been neglecting it.”

I slid a brochure across the desk. On the front was a picture of my father, arm in arm with a group of smiling people in front of a soup kitchen.

“The foundation needs a director of operations. The pay is half of what you were making. The hours are terrible. The office is in a church basement. Your job will be to help people find their footing again. The same people you would have thrown out of the café.”

Steven stared at the brochure as if it were a snake.

“You’ll be working directly with the people you despise,” I said. “You’ll hear their stories. You’ll see their faces. You will be forced to look at the very thing you’ve been running from.”

This was the real twist. Not my identity, but his fate.

“Why?” he asked, his voice raw. “Why would you do this?”

“Because my father believed that everyone deserved a second chance,” I said. “And because I think the best way for you to fix what’s broken inside you is not to be punished, but to be put in a position where you have no choice but to learn empathy.”

“And if I say no?”

“Then we shake hands, and you walk out that door. Your career is probably ruined in this city, but you’re a smart, driven man. You’ll land on your feet somewhere else. The choice is yours.”

He sat there for a full five minutes, staring at the picture of my father. I could almost see the war raging inside him.

Finally, he picked up the brochure.

“I’ll do it,” he said, his voice quiet but firm.

Over the next six months, I threw myself into revitalizing The Daily Grind. I visited every single branch. I promoted Maria to a regional training position, teaching new managers the “Pendelton Way.” We brought back all the old community-focused initiatives.

Profits dipped slightly at first. Then, something amazing happened. They began to climb higher than ever before. People wanted to be in a place that felt warm, that felt like a community. The numbers followed the soul, not the other way around.

I didn’t hear from Steven directly, but I got reports from the foundation. The first month was a disaster. He was rigid, cold, and ineffective. The board wanted him gone. I told them to give him time.

The second month, something shifted. He organized a clothing drive that was a huge success. The third month, he spent a week personally helping a veteran navigate the bureaucracy to get housing assistance.

One evening, I decided to visit the church basement that served as the foundation’s headquarters. It was late, but the lights were on.

I peeked through the window. Inside, Steven was sitting at a folding table across from a young woman who was crying softly. He wasn’t wearing a suit. He was in a simple sweater and jeans.

He was listening to her. Truly listening. Then he pushed a cup of coffee across the table toward her and began speaking, his voice low and kind.

He didn’t see me. I just watched for a moment, then walked away.

The coat my father had left me still hangs in my office. Sometimes, when I’m getting lost in the spreadsheets, I touch its rough fabric. It reminds me of the dirt, of the tile floor, of the look on Steven’s face.

It reminds me that a person’s worth is not determined by the clothes they wear or the money in their pocket.

Kindness is not a passive quality. It’s an active choice. It’s the decision to see the person, not the problem. It’s the hardest, most important work there is, and it’s the only investment that offers a truly rewarding return.